- The hypothesis of the invention of the battery is very unlikely both scientifically and historically, even if we can always imagine that we add elements to an object to make an electric battery.

- The gilding of metallic objects by electrolysis would suppose that we had, in Antiquity, gold salts in solution, which is even less likely.

A MYSTERIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL OBJECT

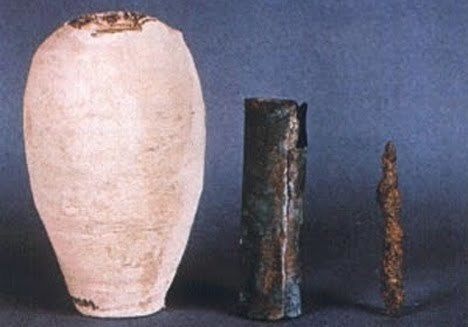

In 1936, archaeological

excavations of a necropolis to the south-east of Baghdad brought to light,

among several hundred objects, glassware, earthen figures, engraved tablets,

etc. a curious collection that can be dated from the Parthian period, between

the first century before and the first century after Jesus-Christ. Inside a

terracotta vase about fifteen centimeters high, the neck of which, chipped,

bore traces of bitumen, were

- a copper tube whose bottom was covered with a thin

layer of asphalt

- the rest, very rusty, of an iron rod

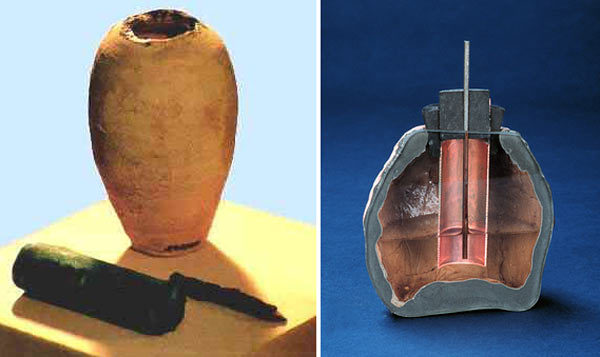

This set, after passing

through various intermediaries, arrives at the Austrian archaeologist Wilhelm

Koenig, then director of the Baghdad museum. He emits the idea that once

brought together, these elements constitute an electric battery, of which he reconstructs

the diagram: to complete it, he wrote in 1938, it suffices to pour a saline or

acid solution into the copper tube.

Indeed, two metals of

different nature immersed in an electrolyte, such is the principle of the

battery, invented by Alessandro Volta in 1800.

Koenig supports his

hypothesis of an electric battery by the observation, without a priori

relation, of a rudimentary technique of electroplating, used in the 1930s by

the silversmiths of Baghdad to gild jewelry.

These silversmiths used

the device shown in the battery. This is a battery, short-circuited, inside

which the desired chemical reaction occurs. During this reaction, metallic gold

from the solution of a gold salt is deposited on the object to be gilded D. The

process could well, suggests Koenig, have a much older origin. But this device

has little to do with the mysterious vase. The only link, not explained by

Koenig, is that it would provide a second testimony to a mastery of electricity

by the Parthians.

The process also

supposes the use of gold salts in solution, which in Antiquity is extremely

hypothetical. Gold does not oxidize and is only found in nature in the metallic

("native") state in gold nuggets or, in traces, in a few rare ores.

Before medieval alchemy, we do not know of a method allowing to

"dissolve" gold - that is to say to make it pass to the state of

soluble "salt", by a chemical reaction.

Let's go back to the

mysterious object from 2000 years ago. Not long before, several similar objects

had been unearthed in another excavation in Mesopotamia. The copper cylinders

inside the pottery contained plant fibers suggesting to archaeologists the

remains of papyrus scrolls. But Koenig emits the idea that these pottery could

have been put in series, as batteries, in order to increase the electrical

voltage delivered. And he goes even further by highlighting the existence of

older bronze and copper vases which, according to him, could have been gilded

by electrolysis with these batteries in series.

It remains to be

specified which electrolytic gilding device would have been powered by such a

battery of batteries. All electrolytic devices for gilding, the first having

been developed around 1840, are based on the use - again very problematic in

Antiquity - of dissolved gold salts.

In 1939 Willy Ley, an

American engineer and popularizer of science popularized Koenig's idea in a

science fiction review. The second world war occurs and the "piles of

Baghdad" remain in the shade for some time.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE "ELECTRIC" INTERPRETATION

After the war, an

American researcher of the company General Electric, Willard Gray, tries the

first reconstitution of the "battery of Baghdad" according to the

indications of Willy Ley and obtains a weak electric current. Willy Ley said he

was convinced "that at the time of Christ, we had galvanic batteries in

Baghdad". Other experimenters engage in reconstitution and show the

possibility of obtaining a weak electric current with different solutions

(grape juice, lemon juice etc.).

In 1978, the

archaeological object was presented in an exhibition on Iraq at the Roemer and

Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, and the catalog bluntly explains that

the Parthians invented the battery long before Volta. A television report

increases the credibility of the matter by showing a technician in a white

coat, in front of the device.

Arne Eggebrecht,

director of the Museum, manages, by assembling a battery of these reconstituted

"batteries", to cover a metallic object with an extremely thin layer

of gold. But the experiment has not been published, and one wonders what type

of electrolysis allowed the gilding.

This does not prevent

the "electric" interpretation from being very popular today, it is

only to surf the Internet to realize it. In 2005, MythBuster (literally

"myth breaker"), a Discovery Channel flagship show hosted by two

specialists in special effects, reproduced the experience of gilding in front

of viewers and deduced that the Baghdad stack hypothesis is "plausible".

By an adventurous

association of ideas, the connection is sometimes made with a bas-relief of the

temple of Denderah in Upper Egypt, on which some do not hesitate to see a

foreshadowing of electric bulbs or discharge tubes. After Volta, it's now Edison

who has to worry about! The battery and electric lighting would therefore only

have been "re-invented" in the 19th century after several centuries

of obscurity.

The affair brings into

play several springs of popular science, the mystery, the spectacular, the

discovery of hidden ancient knowledge, and a certain thirst for

"revenge" on official science.

YES, BUT HERE IT IS...

Several objections are

opposed to these interpretations. We have already mentioned some of them.

Koenig suggested that

the method of the silversmiths of Baghdad in the twentieth century was the

continuation of ancient skill. But Gerhard Eggert recalls in 1995 that this

method was described in the English patent for electroplating filed in 1839. No

prior art is known to this process.

Archaeologists have also

shown that ancient jewelry could be plated using very fine gold leaf, this

delicate technique being well mastered by goldsmiths in the Middle East 2000 years

ago. Mercury gilding using an amalgam (a liquid gold-mercury alloy) was also

known at the time.

As for the gilding

experiment which would have been carried out, but not published, by Arne

Eggebrecht, we do not know the details. We can only be surprised at the result

announced. Our experiments, in agreement with the theory of electrolysis, show

that one cannot obtain gilding by electrolysis without gold salt in solution.

Paul T. Keyser imagined

another electrical application for the mysterious vase, already mentioned by

Koenig: a medical use of the current produced, possibly in a religious context.

But the voltage delivered by a single "battery" is much lower than

the values to which the human organism is sensitive when applied to

the skin.

Finally, as science

historian Allan Mills points out, the object itself seems to agree with

difficulty with the hypothesis of an electric battery. There is in fact the

absence of metal wires essential to conduct the electric current. If this

absence can be explained by a disappearance linked to the age of the objects,

the presence of such wires does not seem to have been foreseen: the bitumen

plug, which permanently closes the vase, prevents the exit of a conductive

wire. from the copper tube and makes frequent replacement of the electrolyte

inconvenient, the composition of which would be rapidly degraded by the

chemical reactions linked to the production of a current.

Generally speaking, the

possibility of an experiment does not prove that one sought to achieve it by

constructing the object. This interpretation is ultimately based only on a

resemblance in form to a modern object (the Volta stack), and not on the

knowledge we have of the way of life of the owners of the object in antiquity.

In the 1930s,

archaeologists had already advanced, as we have seen, the hypothesis that the

vases discovered in Iraq would rather be receptacles intended for the transport

of small rolls of papyrus, perhaps formulas for prayer. Allan Mills proposed a

more prosaic hypothesis: the device could be intended to repair holes in skin

bags, very precious objects for life in the desert. The pointed iron rod,

heated over a fire, allows you to melt a little bitumen from the stopper and

apply it where the skin is pierced! A way to show that imagination can take the

most diverse directions. This interpretation, however absurd it may seem at

first glance, is however inspired by a concrete knowledge of the way of life of

nomadic populations in desert regions.

TO CONCLUDE

The presence in the

mysterious vase of two different metals remains unexplained. The point is that

by adding an electrolyte - and two metal wires - the device can produce a very

low current. However, it would be surprising if this technology remained so

confidential that it left no trace, led to no testimony from foreign travelers,

and finally that it disappeared for nearly two millennia. The battery

hypothesis, which poses, as we have seen, serious technical problems, even if

the experiment is possible, remains to this day historically, archaeologically,

and scientifically unlikely.

0 Comments