STRANGE DANCING EPIDEMICS

It is the story of a

deadly “flashmob” in the Middle Ages which continues to intrigue specialists.

Strasbourg, summer 1518.

In the narrow streets of the city and in the squares, dozens of people dance

frantically to the rhythm of tambourines, violas and bagpipes. But the

atmosphere is not festive. The scenes are even "terrifying", writes

the historian of medicine John Waller in The Dancing Plague (Sourcebooks

editions), a reference work on the subject, published in 2009.

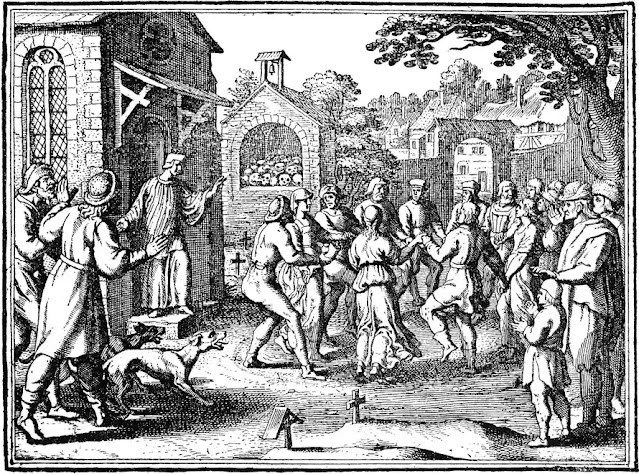

[This picture is collected from Wikimedia Common which is licensed under CC 1.0]

Women, men and children

with this strange “dancing mania” cry out, begging for help, but cannot stop.

They are in a trance. The symptoms are shown as “vague eyes; face turned to the

sky; their arms and legs moving with spasmodic and tired movements; their

shirts, skirts and stockings, soaked in sweat, stuck to their emaciated bodies,

”describes John Waller. In a few days, the cases multiply as a virus spreads,

sowing fear and death in the Alsatian city. Up to fifteen dancers died every

day, according to a witness at the time, victims of dehydration or

cardiovascular accidents.

It was a woman, Frau

Toffea, who opened the ball for this dancing death on July 14. Epidemiologists

would call her "patient zero", the first individual infected during

an epidemic. The fate of this woman was traced by Paracelsus (1493-1541), a

Swiss physician and alchemist, known as one of the founders of toxicology. Fascinated

by this collective episode, he came to the scene in 1526 to investigate.

This July 14, 1518,

therefore, Frau Toffea begins to jiggle, alone, in the streets. Despite her

husband's pleas, fatigue, and bloody feet, she continued for six days and

nights, just interspersed with a few naps. In the meantime, other people have

joined in the dance. As of July 25, 50 individuals are infected, they will be

in total more than 400. The verdict of the doctors is in the direct line of the

humoral theories of the time: the disease is due to a "too hot

blood". The city council then decides to cure evil with evil. Space is

left for the dancers and dozens of professional musicians are hired to

accompany them, night and day.

Serious public health

mistake! By showing off the dancers in this way, the authorities are only

promoting contagion. Faced with failure, the council turned around at the end

of July: the platforms were dismantled, the orchestras banned. But the

phenomenon will not end until a few weeks later, when the dancers will be

escorted to Saverne, one day from Strasbourg, to attend a ceremony in honor of

Saint Guy, protector of patients with chorea (abnormal movements).

After almost five

hundred years, this episode continues to intrigue specialists. Because it is

not a legend. The dancing mania in Strasbourg, which is neither the first nor

the last dance epidemic, is one of the best documented. It is even the only one

to have been able to be reconstituted so precisely, underlines John Waller,

probably because it arrived after the invention of the printing press, in a

city having formalized a bureaucracy.

In total, about twenty

comparable episodes were reported between 1200 and 1600. The last would have

occurred in Madagascar, in 1863. A variant, tarantism, has also been described

in Italy: the disease occurred after a hypothetical bite of the spider Lycosa tarentula,

and dancing (tarantella) was an integral part of the treatment.

Over the centuries,

several scenarios have been put forward to explain the Strasbourg epidemic:

ergotism (poisoning by rye contaminated with a mycotoxin), heretical cult,

demonic possession, or even collective hysteria. For John Waller, context

played a major role. Trance phenomena, he writes, are more likely to occur in

individuals who are psychologically vulnerable, and who believe in divine

retribution. However, these two conditions were met in Strasbourg. The city had

been struck by an unusual succession of epidemics and famines; and its

inhabitants believed in Saint Guy, able as much to inflict as to cure diseases,

by dancing in particular.

THE ANCESTOR OF RAVE-PARTIES?

Could a dance epidemic

break out in the 21st century? Unlikely, according to Bruno Falissard. Today's

conversions are rather gastroenterological or rheumatological manifestations,

“reasonably” compatible with the data of science. This does not prevent the

emergence of collective forms. For example, it is questionable whether the

epidemic of minor forms of gluten intolerance observed in many countries is not

actually a collective conversive manifestation. "

Some dare to draw a

parallel between these dancing manias and the monster rave parties of today

during which the dancers can sway in a trance, at the risk of falling from

exhaustion. But there are some fundamental differences: the use of recreational

drugs is a big part of clubbers' trance. And the latter is probably more

euphoric than the terrified choreomaniacs of the Middle Ages.

0 Comments